My dad’s family came to Greater Cincinnati by way of the Appalachian Mountains. My mom’s people were from out west, specifically New Mexico and Texas. So, I am genetically wired to fall in love with hillbillies and cowboys (basically, I’m screwed). As a girl, many summers were spent out west visiting my mom’s people. I had uncles from Texas who were real cowboys, they spoke with a long drawl, told funny tales and always had a sparkle in their eye and an ornery sense of humor. If civilization would have started in Texas, we may still believe the world is flat, because of the endless skies that seem to go on forever. My Uncle Ray was a cotton farmer in Sweetwater, Texas. Even when I was a toddler, I’d pick up his accent after a few days around him. I will always love cowboys.

Steve Earle’s childhood was spent primarily in San Antonio, Texas. When he was about 17 years old, already crafting songs, he made his way to Houston where he would connect with some of the greatest songwriters in America. Steve was 5-10 years younger than his talented peers. Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark became mentors and Earle has in recent interviews credited Guy and his wife Susanna for finishing raising him. At 19 he left Texas and some already forming vices (too many pretty girls, too much booze) to be more productive as a songwriter in Nashville, where Clark had already headed. In the 1975 documentary, Heartworn Highways, there’s a scene toward the tail end of the movie that shows a jam session at Clark’s home with a young Steve, hair hanging in his face, drinking whiskey straight from the bottle, trading songs. There are some touching outtakes where you can hear Earle being encouraged by his big brothers, Clark and Rodney Crowell, “boy that’s a good one!” Susanna Clark is singing along as well. As a songwriter myself, I know these are the moments of true joy. As a person, I know that you find your mind drifting to these special moments in your life as you get older, when things invariably get more complicated.

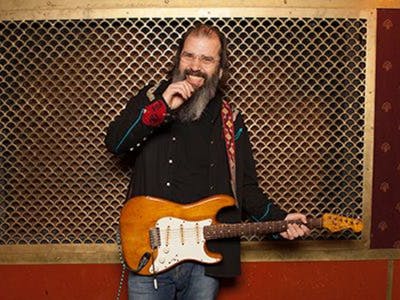

The young songwriter in those clips, is now an icon of Americana music, with an expansive collection of beautifully crafted songs and an incredibly interesting and often messy life story. A few of his brothers have passed on, Townes on New Year’s Day of 1997 and Guy Clark, in May of last year.

Earle at 62, has had some personal hardships in recent years; certainly the death of Clark, an autism diagnoses for his 7-year-old son, John Henry, and divorce from his 6th wife, Allison Moorer. All of these hurts have surely had Earle in the grieving process lately. Men seem to become more tender with age as well, so to be dealing with all of these loses at 60, as opposed to 29 or 30, has likely caused some feelings of vulnerability. Earle has long been candid about his struggles with addiction, a monkey you never really get off your back. Sober or using, addiction stays a centerpiece of the life of an addict. In the context of what has been going on in his life, So You Wanna Be an Outlaw, seems the perfect album for Earle to release.

This album has Texas and Nashville all over it. Earle said it made sense to “come home” to this style right now. Another driving force of the project is, “I’ve gotten to be a better guitar player. This is the first time I’ve been able to sit on the back end of a tele.” Earle credits some of this to his study of Bluegrass throughout his career. “Bluegrass requires a high level of musicianship. If you watch great bluegrass players they finish each other’s sentences.” He said he got to see Bill Monroe play at The Grand Old Opry when he was 7 years old. He was really struck by the intensity of Monroe’s music. “Bill wore a stern expression and expected the same of the guys in his band. You weren’t supposed to smile. They wore matching suits. He wanted the music to be taken seriously.” Earle said he was lucky enough to know Bill Monroe later in his life. A hallmark of Bluegrass Music is the dark nature of the narratives. Somebody is going to die in a Bluegrass song. When I mentioned that to Earle, he chuckled and said he had gone to the Exit Inn in Nashville to catch some bluegrass one night, and his companion noted you can’t get halfway through a bluegrass song without a blade coming out. The songs on Outlaw are not traditional bluegrass, but there is definitely plenty of darkness.

Earle went to Austin to record the album. It is intended to be an ode to “Honky Tonk Heroes”, Waylon Jennings’s well known album that seemed to give the “Outlaw Country” movement in the 70s a kick in the ass. All of the songs on the album, with the exception of “We Had It All” were penned by Texan, Billy Joe Shaver. On Steve’s album, he covers one of those tracks, “Ain’t No God in Mexico”. He ends with Waylon’s, “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way?” one of my personal favorite tracks on the album. “Outlaw Country” is in high favor currently, with a lot of current songwriters taking a stab at recreating that trend. There’s plenty of discourse out there about what the genre really is. To me this is a futile argument. It ain’t the 70s. Outlaw anything in 2017 is going to take on its own characteristics. There’s a lot of great honkytonk on the record, fit for doing the Texas Two Step. Steve commented that based on the dancing going on at shows the album seems to be danceable. “Walkin' In L.A.” with Johnny Bush, is a stand out in this style. Pedal and Steele chat back and forth and Steve and Johnny trade verses as well as croon together. Miranda Lambert makes an appearance on the album on “This Is How It Ends” a song she and Earle co-wrote. This one has more pop sensibilities and the double vocal by Earle and Lambert is imperfect, which makes it great. Both voices stand out distinctly and it’s not mixed with one as the backup. Earle commented that Lambert wrote some of the best lines in the song. Lambert is a gem in the current group of Country artists. She stands out in a genre that for a spell has been pretty homogenized. There’s plenty of grit on the album; “Fixin’ to Die” and the title track both have teeth. The album is rounded out with some great singer-songwriter style tracks, that Steve is the master at pulling out. “The Girl on the Mountain” and “Goodbye Michelangelo”, Earle’s sweet farewell to his dear friend, Guy Clark, are the kick in the chest kind of ballads that Earle seems to write in his sleep.

Earle is known for talking off the top of his head frequently. Recent articles have run headlines that seem to me to be quick bait to get reader’s interests piqued. Oh Steve, no doubt said things like; his wife left him for a skinnier, less talented musician and that a lot of modern country (I think we’re talking about “Bro-Country” here) is like Hip Hop for people who are afraid of black people and that he’d rather just listen to Kendrick Lamar, “I really like him.” I think what these quotes aren’t conveying is that Steve is half joking when he says this kind of stuff. The transparency of Earle himself, is probably what makes him such a treasure as a songwriter and a human. He has been a pretty open book about his struggles and his joyful moments too. He seems to stay in touch with the fact that he is aging in a quickly changing world and he doesn’t have all the answers. He is very vocal about his take on social issues as well as politics, and he often talks on stage about these things (sometimes to the displeasure of some in the audience). Don’t look for Steve Earle to tone it down anytime soon.

Elijah’s Church (from Heartworn Highways)

written in Earle’s late teens

When this race has been run

Take me back where I came from

And let me return what I took from the ground.

When this body won’t carry me no further

Take me back and lay me down

Steve Earle’s voice has stayed authentic and true to who he seems to be as a person. Fallible certainly, possibly brash or arrogant at times, but sweet and genuine and even spiritual in his best moments. Something even his harshest critics cannot deny. So You Wanna Be an Outlaw is another strong effort from the man. I recommend you dig into his entire body of work, like you would the work of his mentors; Van Zandt and Clark. Texans are brilliant storytellers and songwriters. Steve Earle is one of the best.

Catch Steve Earle at The Taft Theatre on Thursday, July 20th!