Back in 2000, I was living in Chicago and taking guitar lessons at The Old Town School of Folk Music. Steve Earle was spending a lot of time in town because his (then-17-year-old) son Justin had moved to Chicago to figure out what he wanted to do with his music career. Since he was spending so much time in town, Steve decided to hold a songwriting class. I was lucky enough to get in. Over the course of several weeks, he traced a path that linked his work with Harry Smith (and The Anthology of American Folk Music compilation), Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Townes Van Zandt and many others. He was very open about his influences and said that that there are no new cadences, but you could always find new ways to express yourself. Stories matter. Songs matter. Times were good, the economy was booming as people wrapped their heads around the nascent internet and what it could do. One week, Steve was drinking his coffee before class. As we chatted, he made an offhand remark that people were used to things being good and hard times were going to come again. We laughed and got on with class. Over the next eighteen months, the tech bubble crashed, there was a contentious Presidential election and 9/11 threw the world into turmoil. It was the beginning of a whipsaw cycle of ups and downs that continues to this day.

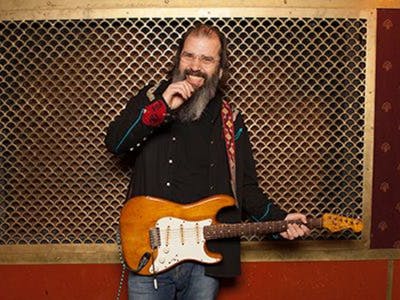

In the last eighteen years, Justin became a successful artist in his own right, Steve got married (again) and divorced (again), had another son, moved to New York, put out two books, wrote and produced an off-Broadway play, acted in film and TV projects, made eight studio albums and continued on a tour that occasionally pauses but never really stops. Along the way, we lost many of the voices that helped shaped Steve’s work including Irish poet Seamus Haney, Waylon Jennings and, more recently, Guy Clark. Last year Steve released his sixteenth studio album, the terrific So You Wannabe an Outlaw. The new album has a beautiful simplicity and directness to it. He embraces and acknowledges his influences head on. It feels like the perfect fit for a world that’s become even more chaotic and complex than we could have imagined at the turn of the century.

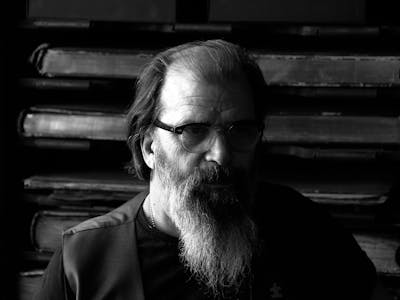

He’s about to kick off a tour with The Dukes to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Copperhead Road, but last night we were fortunate to have Steve all to ourselves in the stunning Mercantile Library. It’s a gorgeous space, huge but intimate, a blend of glass, warm wood and metal. Thousands of volumes of words surround us and the remainder of the evening light filters through the tall arched windows as Steve takes the small stage.

Over the course of the evening, Steve alternates between singing songs (highlights include “Devil’s Right Hand”, “Guitar Town” and “Someday”), telling stories, and reading passages from his two books (Dog House Roses and I’ll Never Get Out of Here Alive). He jokes that he’s working on his autobiography but can’t bring himself to finish it because he’s so boring.

It’s striking when Steve juxtaposes songs with his longer stories. The compactness and clarity of what he can accomplish in a few minutes is evident when he performs “Taneytown” (from the classic album El Corazon). The song was inspired by Neil Young and Crazy Horse. He worked on the song, then wrote the longer story and revisited the song with a better idea of what he wanted to say. The electric version on the album is ominous and you can hear the influence of Crazy Horse in the snarling guitar, but the acoustic version is just as powerful.

In the course of a few minutes he tells the tale of a young African-American boy in the south who goes into town against his mother’s wishes, gets attacked by four white boys and ends up stabbing one with his Randall knife. He drops it, one of the boys picks it up and later gets hung for the crime. When Steve reads the longer story from Doghouse Roses, you get more of the character development and back story. It’s richer in parts, but it’s startling how much of it comes through in the much shorter song.

Death weighs heavily on his new album as well. Earle has explored the theme several times in his career, but there are shades that a younger Steve may have had difficulty finding. The most startling beautiful example is his simple acoustic tribute to Guy Clark (“Goodbye Michelangelo”). Over a simple finger plucked pattern (reminiscent of Townes van Zandt’s “Lungs”), he says goodbye to Guy and wonders when his own time is coming.

Steve wraps up with a rollicking version of “Copperhead Road”, one of the few tunes from Copperhead Road that has stayed in his set for thirty years. It’s another prime example of his storytelling - a blazing Celtic-metal romp about bootlegging and the Vietnam vet who wants to diversify the family business into drugs.

After the concert, Steve takes a few questions from the audience. He talks animatedly about his work on Treme and The Wire, and a few of his songs. In a recent interview, Steve said he had to be 60 to write the songs on the new album. I asked him if he looks back at Copperhead Road after thirty years and is surprised by something his younger self did on the album. He says the biggest surprise was playing it again and realizing that because they mastered the song for vinyl, it has two sides. Side 1 is the political, post-Vietnam era side but Side 2 is “all the chick songs”. He chuckles and jokes that after listening to Side 2, he now realizes why he got married so many times in the ‘80s.

Steve heads over to sign books, CDs, and even an acoustic guitar. He chats happily as he signs. I remind him of the comment he made back in Chicago about hard times. He nods and then spiritedly talks about the current state of the world and the need for change. But he also allows that he’s optimistic for the future and things will change again.

Hearing his words and music last night, it’s hard to doubt him.