I.

To say that the Internet killed the “regional” band is to make a perfectly reasonable assertion. We know this not so much as a hard and fast rule, but as a general observation that mostly works.

In the years before AOL inundated our mailboxes with software installation discs, we frequently used an artist’s locale as our most reliable signifier; the name of your city or state or small town was shorthand for your style. Most of our favorite artists introduced themselves at shows by saying things like, “We are a band called Fugazi from Washington, D.C.,” and they told us that because in the off-chance that we didn’t know who was actually on stage, we all knew what it meant to be from Washington D.C. That information alone gave us a sense of what they stood for, who they revered, and if not what they would sound like, then certainly what they wouldn’t sound like. The same could be said for bands from New York or Louisville or Seattle or Minneapolis or Detroit. There were always outliers, of course. But in this era before hyper-connectivity, different regions were allowed to take time in developing their own disconnected styles of playing music long before the rest of the world could hear it. Each region invented its own fashion sense, its own cultural heroes, and in the case of punk, even its own unique style of slamdancing — and they were able to do that in relative isolation because there was no fear of people in Paris watching the video on YouTube later that week.

Which is why, if you look for it, you’ll notice that as soon as our musical experience became firmly entrenched online — at some point in the early millennium — our signifiers changed. Fewer artists introduced themselves as representatives of their cities anymore. Global communication demanded a more universal lexicon, and with that, we chose to herald the shaky planks of “genre” as solid ground.

II.

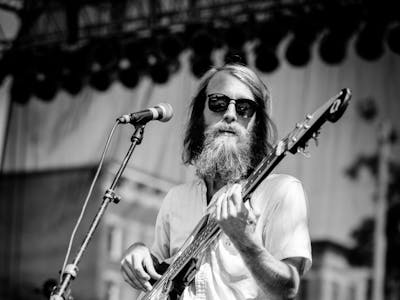

Evan Weiss has spent much of the last eight years preoccupied with place. Recording under the name Into It. Over It., Weiss has already dedicated an entire album to the American city (Twelve Towns), in addition to writing countless songs named after geographical positions both general (“A New North-Side Air,” “Connecticut Steps”) and painstakingly specific (“Midnight: Carroll Street,” the entirety of a split LP with Koji named after five small Chicago neighborhoods). In fact, if you were to quickly run through the track listings for his entire discography, you’d be hard-pressed to find a single release that fails to make this connection explicit in some way. Even a cassette-only covers EP manages to include The One AM Radio’s “Ghost on the East Coast.” And that’s just the song titles.

That the emergence of Into It. Over It. and its subsequent fixation with “spatial exploration” — the name of a song on Intersections, if you’re keeping count — seems to neatly coincide with Evan’s move to Chicago in 2008 is more conspicuous than coincidental. We tend to think more about place when we’re feeling displaced.

III.

Chicago is a central city, in more ways than one. Historically, the music community there has always taken advantage of its own cultural, political, and social in-betweenness in a manner so distinct that its regionality subsumed otherwise arbitrary classifications. Chicago Blues, Chicago House, Chicago Jazz. These aren’t offshoots as much as innovations.

At its core, the “sound” of Chicago’s music community has always capitalized on its physical and ideological distance from the East and West Coast wings of industry; its creative tendencies lean more towards freedom than formula, more towards hybridity than homogeny. It’s the reason why Marshall Jefferson and Steve Albini could each discover Roland drum machines in the 1980s and wind up with records as disparate as “Move Your Body (The House Music Anthem)” and Songs About Fucking, and why many locals didn’t feel a need to choose one over the other.

IV.

Standards is the third “official” Into It. Over It. album. It’s an album that was written in a cabin in Vermont and recorded in San Francisco, on opposite ends of the country, and yet it’s also somehow a record so thoroughly Chicago that — in the way most great Chicago records do — it exposes a breach in genre classification. From the onset, Standards delivers a newfound openness that yields the kind of hybridity most associated with Weiss’s adopted city. It’s a position where skittish post-punk evolves from a Rhodes electric piano; where ambient post-rock drifts alongside a low-slung jazz groove; where Fahey-styled fingerpicking gives way to sharp and angular distortion. “We went into this record intentionally unprepared, and I have never done that before,” Weiss recalls, and this is probably the point. Cohesion happens in the process, not the product.

None of this, Weiss says, could have been possible were it not for the creative culture fostered by John Vanderslice (Spoon, Mountain Goats, Death Cab for Cutie), who ultimately produced the album at Tiny Telephone Studios and later called Evan “one the most challenging and surprising songwriters I’ve ever worked with.”

That’s the other thing: By allowing his music to become more playful and improvisational, Weiss has also become a more honest songwriter. He sounds free.

V.

Standards is the first Into It. Over It. album to feature a track listing devoid of any explicit references to a geographical location. A song called “Who You Are ≠ Where You Are,” however, comes ironically close.